| | NEWS

Elul in Novardok

by HaRav Moshe Eliezer Schwartzbord

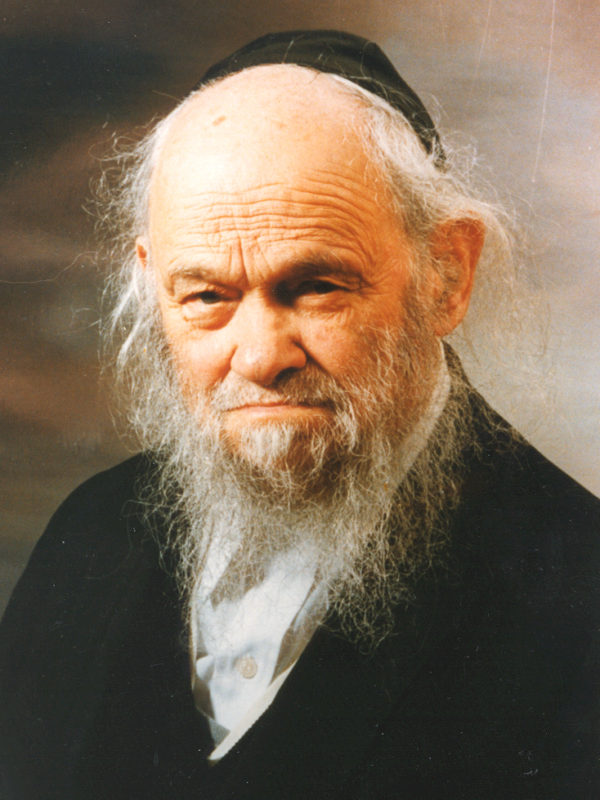

HaRav Ben Tzion Bruk, rosh yeshivas Novardok Yerushalayim

From his personal diary of the Yomim Noraim in 5697 in Beis Yosef of Pinsk. This article was published in the print edition in 1996 and is now published online for the first time.

Part 2

The Parable of the Lost Prince

A king and his only and beloved son once went hunting in a thick and winding forest. They were joined by an entourage of noblemen. While all were engrossed in the hunt, the prince accidentally lost his way. The king called to him, but received no answer.

All that the king heard was his own voice, echoed by the cruel forest. The prince, too cried: "Father, father, pity me!" But his cries were not heard by the king. All of the searches and the promises of reward to whoever found the child, were of no avail. The prince was nowhere to be found.

The next morning, a farmer, who happened to be passing through the forest, found the child lying on the ground, in a state of torpor. The farmer was delighted with his find of a young boy, for now he would have someone to look after his ducks. He brought the frightened child home, fed him a sparse meal, and cursed him. The child shouted: "I am the king's son." But the farmer continued to beat him.

At last, the child stopped saying that he was the king's son, and resigned himself to his bitter fate. In time, the child completely forgot that he was the king's son. From day to day, he languished away in the muddy swamps and raised ducks.

But the king did not despair of finding his beloved son. He went from village to village in search of him. Whenever he reached a village, he would announce: "All the villagers are invited to appear before me. Each will receive gifts and whatever help he needs."

At last, the king reached the farm where his son was living. There, too, he made his announcement, and each villager approached him with a request, one asking for a new wagon, another for a cow, and yet another for new furniture for his house.

The king's son also made a request. He asked for a pair of boots, because the winter in the village was very harsh. He also asked for a warm hat and jacket and two loaves of bread. Although the child's clothing was torn and ragged, the king recognized his voice, and burst into tears of joy. "You are my lost son," he cried out. "You will have everything. Come home with me to the palace. You won't lack a thing. Don't ask for bread and boots! You're a prince."

The nimshal: Now the words of Dovid Hamelech, "The Lord is my light and my salvation, whom shall I fear...One thing have I asked of the Lord, that will I seek: that I may dwell in the house of the Lord all the days of my life" (Tehillim 27: 1,4), are understood: Instead of asking for a pair of boots, a warm hat and jacket, I ask to dwell in Your palace all of my days, for then all of my requests will be fulfilled.

The Moshol of the Verse, "Seek the Lord when He is found; call to Him when he is near."

This verse brings to mind the story of a man we will call Thomas, an inhabitant of a certain country who violated the king's will and was about to be tried in the royal court. The man hired advocates and wrote the king letters in which he pleaded for mercy and forgiveness.

Soon something unusual and sad became clear to Thomas. He learned that a while ago, the king had disguised himself as one of the people. And where do you think the king had lodged for an entire month, if not in Thomas' very own home?

This, though, became known to Thomas only after the king had returned to the palace. Only then did Thomas realize that he had spoken with the king on a daily basis, and that, had he pleaded with him face to face, the king would have forgiven him. "What an opportunity I have lost," he said.

Thomas was very upset, and burst into tears. "Why am I writing letters which arouse pity, when I could have spoken to him personally? Woe is me! Why did I let such a chance slip through my fingers?"

The nimshal: During the awesome days of Elul, the month of rachamim and selichos, as well as during aseres yemei teshuva, HaKodosh Boruch Hu dwells amidst us. During this month, we can effect changes which generally take a long time to set into motion, as it is written: "Seek the Lord when he is found; call to him when He is near."

HaRav Gershon Leibman, rosh yeshivas Novardok France

As Long as the Candle Burns, One Can Still Fix Things

Late one Elul night, R' Yisroel Salanter passed by a shoemaker's house, and saw that a light was still burning inside. Drawing near the dusty window, he saw a weary shoemaker seated on a stool. In his left hand, he held a shoe. In his right had was a hammer. A nail had already been inserted in the shoe's sole. His family stood beside him, pleading, "Go to sleep...Rest a bit."

But he replied: "Now is not the time to sleep. As long as the candle still burns, one can still fix things..."

R' Yisroel Salanter incorporated this maxim into his mussar study and many times repeated: "As long as the candle still burns, one can still repair."

It's a pity to waste even one moment during Elul. In Elul, each moment is precious. Each moment in Elul provides an opportunity to achieve and correct. There are those who acquire their share in the World to Come in one hour.

Why are you sleeping! Awaken... Call out to HaKodosh Boruch Hu: Ovinu Malkeinu, ein lonu melech ela Oto — Our Father, our King, we have no king but You!"

Novardok Jerusalem

Elul in the Novardoker Yeshiva of Yerushalayim

By his grandson, Rav Shimon Bruck

The Rousing Voice is Silenced

It is Shabbos in Yerushalayim. The sun still hasn't set. The Jews of the sacred city are streaming to the mincha services in synagogues and shtiblach. Those who have finished their prayers are rushing home for seuda shelishis.

However, during the month of rachamim and selichos, things are different, and both individuals and groups from all parts of the city — from distant Bayit Vegan in its western part, to nearby Beis Yisroel, are streaming toward the Beis Yosef Novardok Yeshiva which nestles on a slope over looking Shmuel Hanovi Street.

This throng consists of a Jews from many backgrounds: Israelis, alongside Jews from abroad, Lithuanian Jews beside Chassidim, gedolei Torah, avreichim, baalei battim, and yeshiva students, both Ashkenazim and Sephardim. They are all rushing to the mussar discussion of the gaon and tzaddik, R' Eliezer Benzion Bruck, rosh yeshiva and founder of Yeshivas Beis Yosef Novardok in Yerushalayim.

The discourse is called for shekia. However prior to its delivery, a mussar session is held. The small notices posted in the various neighborhoods inform the public of this schedule. "Small notices," says one of the great mashgichim of our times, "which are rife with meaning!"

A long time before the beginning of the mussar session, the gaon, R' Benzion Bruck is seen climbing the staircase leading to the beis midrash on the top floor. With one hand, he grasps the rail, and with the other, a thick mussar sefer. He walks slowly. As he enters the beis midrash, an awesome sight greets his eyes, and his heart bursts with emotion.

The beis midrash is filled from wall to wall with bnei Torah, who are swaying back and forth and studying mussar with great fervor. When he enters, they rise in his honor — Torah's honor.

Immediately, the sound of mussar study spreads again throughout the hall, and the traditional melody from which he imbibed his yir'a and fervor, fills the air — the original melody chanted in Novardok, when he was young, the melody to the words: "Olam hazeh domeh leprozdor; hachein es atzmecha beprozdor, kedei shetikoneis letraklin — This world is like a vestibule; prepare yourself in the vestibule, so that you will be able to enter the main hall."

The very sight is sufficient to arouse one to do teshuva. "Just seeing R' Benzion learning mussar is an inspiring experience," says one of his students.

The clock indicates that the time to begin the discourse has arrived. R' Benzion rises. A hush descends on the beis midrash. Many more bnei Torah squeeze inside. All of the benches are occupied. Extra chairs are brought up from the dining room. In the ezras noshim are scores of women who have come to be inspired, too.

The gaon, R' Benzion stands in his place. Beside him is a pile of books which have been arranged in advance. He opens with inyonei deyoma on the parsha, and the mussar teachings derived from it. Slowly, he goes on to other topics, and while leafing through his books on his table — gemoras, sifrei poskim, the Tanach and midroshim — he brings more examples and illustrations of his point.

For an hour and a half, he gushes like an overflowing well, streaming forth rivers of Torah and mussar. Each saying bolsters his intended aim of stressing the need to increase our mussar study and arouse ourselves to repent.

As Shabbos draws to a close, this part of the discussion ends with the summarizing of its main points. The lights have gone out, and total darkness reigns in the beis midrash.

It is pitch dark. The entire audience rises and draws closer to R' Benzion. In the heavy darkness, his voice is heard, and a fervent crying and a heart-rending niggun fills the air.

"Morai verabosai," he says as he stresses the great merit of gathering together a few days before Yom Hadin. "Ask Hashem Yisborach for siyata deShmaya. Let us recite together: Ovinu Malkeinu. Let this hour be one of rachamim and grace before You."

The entire audience lifts its voice too, and with weeping and much emotion, cries out: Ovinu Malkeinu.

"Morai verabosai," he continues, "one needs siyata deShmaya, in order to be drawn closer to Hashem and to be helped to return to Him beteshuva shleima."

Then he raises his voice, and turns to the audience: "Let us ask with a sincere and full heart: Al tashlicheini milefonecha, veruach kodshecha al tikach mimeni — Cast me not away from Your presence, and take not Your holy spirit from me" (Tehillim 51:13).

At this point, the words of arousal proceed on a practical plane of conclusions and future resolves, inspiring the audience — each on an individual basis — to strengthen himself in Torah, yir'a and the study of mussar. He then turns to everyone standing before him, and asks that each person pray with great intention for himself, his family, his acquaintances and friends, and for klal Yisroel which needs much mercy. He says this in a booming voice which emanates from the depths of his heart and his innermost soul, while the entire audience replies: "Hashiveinu Hashem eilecha venoshuva. Chadesh yomeinu kekedem."

The huge throng which fills the beis midrash prepares to recite ma'ariv. The eyes of all are red from crying. Bnei yeshiva, even many who do not understand Yiddish, have also come to hear the words of his'orerus. They say: "The very atmosphere is electrifying. The very chanting of the verses, the weeping and the niggun arouse one to teshuva. "

Even though they don't understand the words, they understand their meaning.

It is still dark inside. The lights don't go on. The shliach tsibur chants: "Vehu rachum yechapeir avon," and the ma'ariv service of motzei Shabbos sounds like the ma'ariv service of Yom Kippur, after Kol Nidrei. The beis midrash quakes from the shouts of: Omein; Shema Yisroel; Omein; Yehai shemai rabbah. The sounds reverberate in the distance. The residents of the Bucharian quarter, who, since the yeshiva was established in their neighborhood many years ago, have grown accustomed to such prayers, listen in awe to the echoes of the ma'ariv service of a motzei Shabbos in Elul.

Elderly people who in the past studied in Novardok or had visited the Novardoker yeshivas of Europe, recall the days in which Novardoker roshei yeshiva would deliver divrei his'orerus. During those moments, they feel that they are back in Novardok, Bialystok or Mezrich.

After the Shemoneh Esrei prayer, the lights are turned on, and an awesome sight is revealed. Many still haven't completed their prayers. The atmosphere is very warm, and at the end of the prayer service, advantage is taken of the emotion charged ambience and a number of chapters of Tehillim are recited.

Afterwards, a long line slowly advances toward the mizrach, and all approach R' Benzion, and with much feeling and awe, wish him a gut voch. Many linger on in order to clarify some points or to ascertain the sources of some of the midroshim he mentioned. Even though R' Benzion is exhausted from his long discourse and divrei his'orerus, he listens to each question, and explains each issue. He also takes the time to ask each questioner where he learns and blesses him with success.

These remarkable his'orerus rallies continued until the Yomim Noraim of 5746. Our generation merited a genuine me'orer in its midst — the sole bearer of the Novardoker mussar method, who for fifty consecutive years followed in the footsteps of his great mentors. He was the only one in Eretz Yisroel who continued to uphold the Novardoker traditions of Elul.

Marveling at R' Benzion's resolve, a noted Yerushalaim talmid chochom said: "It is amazing how fifty years ago, the thirty-year-old R' Benzion stood up and delivered a his'orerus before some of Yerushalayim's most venerable gedolim, such as the famous tzadikim, R' Shmuel Shenker and R' Shlomo Bloch. Even during his final year — 5746 — when he was very weak and only a few days before his death, bnei Torah of Yerushalayim merited to hear his voice reverberating with mussar and his'orerus.

When he died, on Erev Succos 5746, many said that the Angel of Death could not vanquish him before he had completed his his'orerus rallies for the Yomim Noraim.

During the subsequent Yomim Noraim, many wondered: Who will arouse us to teshuva this year? To whom will we go in Elul? But their questions remained unanswered...

Stones from the wall cry out. The walls of the beis medrash shout: Where is the pitch darkness, the crying, the tears and the words? Where is the ma'ariv prayer which shook the entire neighborhood? Where is the "gut voch" and the "gut yohr with which he blessed us?

Where?

We may take comfort in the knowledge that in the yeshiva shel ma'alah he is standing before the Heavenly Throne and arousing Heaven to pity bnei Torah and klal Yisroel, so that we may merit siyata deShmaya, and return beteshuva shleima, and be blessed with a good year, both spiritually and materially.

|